Our cat Xoco arches his back into a bow, fluffs out his tail, and yowls. He holds the pose for a moment, relaxes, and pads off to the kitchen to see whether I’ve dished out supper for him and his brother Quetzal. I’m glad I have: even the cutest kittycat can be a little scary when it takes up the classic Halloween stance, with its ears pinned back, its eyes gone slitty, and its toothy mouth wide open to let out a menacing cry that means “Pay attention to me, or else!” It’s no wonder that in medieval folklore, witches often choose cats as familiars (see the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, one of whom had a cat named Greymalkin, who served her as Satan’s go-between.

So I couldn’t let the spooky season go by entirely without retelling an ancient story about our double-minded (and double-jointed) feline companions. The origins of the tale are obscure, but it goes back at least to the Middle Ages.

A traveller on his way home sees a clowder of cats accompanying a bier upon which is laid the body of another cat, dressed in royal robes and wearing a crown. It seems to be a funeral procession, for the cats are meowing piteously as they walk slowly along. When the traveller reaches his cottage, he finds his wife sitting by the fire with the housecat in her lap. He tells her about the strange encounter. As soon as he has finished his account, the cat stands up and cries, “Then I am the King of the Cats!” He flies up the chimney, and is never seen again.

There are other versions of the legend, but they all convey the same message, which is similar to the one in Kipling’s Just So Stories, “The Cat That Walked By Himself.” Cats agree to live with humans for totally selfish reasons, though if their needs and demands are satisfied, they can be wonderful companions. But they reserve the right to break the agreement at any time, rather like self-absorbed men or women who won’t commit themselves to long-term relationships.

My wife and I (and yes, we’re in a long-term relationship which has weathered a few storms but still sails on) love our two Siamese cats, and to some extent they return our love. But they’re not dogs, whose love is unconditional even if their owners mistreat them. Xoco and Quetzal, like the four other cats who have deigned to live with us over the years, regard us dispassionately. So long as we keep them warm and fed, brush their coats from time to time, clip the toenails they haven’t worn down by clawing the rugs or the furniture, and tend to them when they get sick, they reward us by purring and curling up in our laps. They even lick us with their rough tongues, as if we were their kittens.

But their affection can be withdrawn at any moment, for reasons only they know. Even a fixed male or female cat might live with you for years, and suddenly decide to go off about its own feline business, like the King Cat in the tale. At our New Hampshire house, before we let the Rowdy Boys (a nickname they acquired as kittens, and still live up to) outside, we put them in harnesses attached to long leashes, to make sure they don’t scurry up trees or simply vanish into the woods. Even on the leash, Xoco once managed to pounce on an unwary sparrow before we could stop him. The bird flew away, but with some difficulty, and I doubt whether it lived for very long afterwards.

Cats are, after all, pure predators. Statistics prove that sweet little domestic pussies, when allowed outside unsupervised, are chiefly responsible for the decline in songbird numbers across the world. And of course they gleefully slaughter mice and other small mammals. Xoco, the more avid hunter of the pair, goes after chipmunks and voles whenever he sees them on the ground. He’s caught one of each, and it’s taken some persuasion to make him let go of his prizes.

I remember the hunting style of our first pair of Siamese, Chispas and Celery. Before we got our New Hampshire cabin, we used to spend a week in August at Patsy’s family’s ski house in Vermont, which they rented, cheap, to relatives during the off season. It was an old farmhouse with a long back porch, and atop one end of it there was a loft where a family of phoebes lived. Chispas was a boistrous, aggressive male, older than Celery, whom he treated as if she were his kitten. The phoebes drove him nuts each time they emerged from the louvers of the loft window to swoop across the back yard. He’d leap several times his own height trying to snag them on the wing, and he’d try to claw his way up the side of the house to get them as they flew back. Never any luck.

Quiet Celery ignored Chispas’s fruitless efforts. She kept her attention on the birds themselves, and she figured out that there was another window, without louvers, on the other side of the loft. So one morning, as Patsy and I were sitting on the porch drinking coffee and feeling a little sorry for Chispas, we suddenly noticed that Celery was gone. In a mild state of panic, we got up to begin looking for her. But she reappeared as quickly as she had vanished, with a dead bird in her jaws. Instead of taking it away and devouring it, she deposited it at our feet. Chispas might have thought she was his kitten, but Celery regarded us as her kittens, and had dutifully given us her kill. She looked highly offended when she was met with scolding instead of thanks, and stalked away with her tail straight in the air. Of course she went on attacking the poor phoebes, and eventually they moved out of the loft to look for less perilous housing.

It’s the predatory instinct that has given cats a bad reputation over the centuries, even though that same instinct has proven useful to people when it targets mice and other destructive vermin. Even ailurophiles remain just a little bit wary in the presence of what Shakespeare called “the harmless, necessary cat.” (Shakespeare was good at irony). We never forget that felis domesticus is a close cousin of lions and tigers, animals who have regarded humans as lunch since the Pleistocene Epoch, and still do, in rural parts of Africa and India. But they won’t for much longer. Thanks to human overpopulation in both regions, all-out war has been declared against them by local farmers, and despite the existence of wildlife preserves and armed rangers to patrol them, poachers continue to exact a bloody toll. Habitat loss and inbreeding add to the problem, and most biologists predict that the biggest of the felids will soon go extinct in the wild.

The small ones will survive, however, because as Kipling pointed out, they have adapted quite adventitiously to living with humans, and the advantage is mostly theirs. In return for keeping our houses vermin-free and acting like adorable fur-balls, they get food without hunting for it, and shelter without having to find safe places outside where bigger predators can’t get at them.

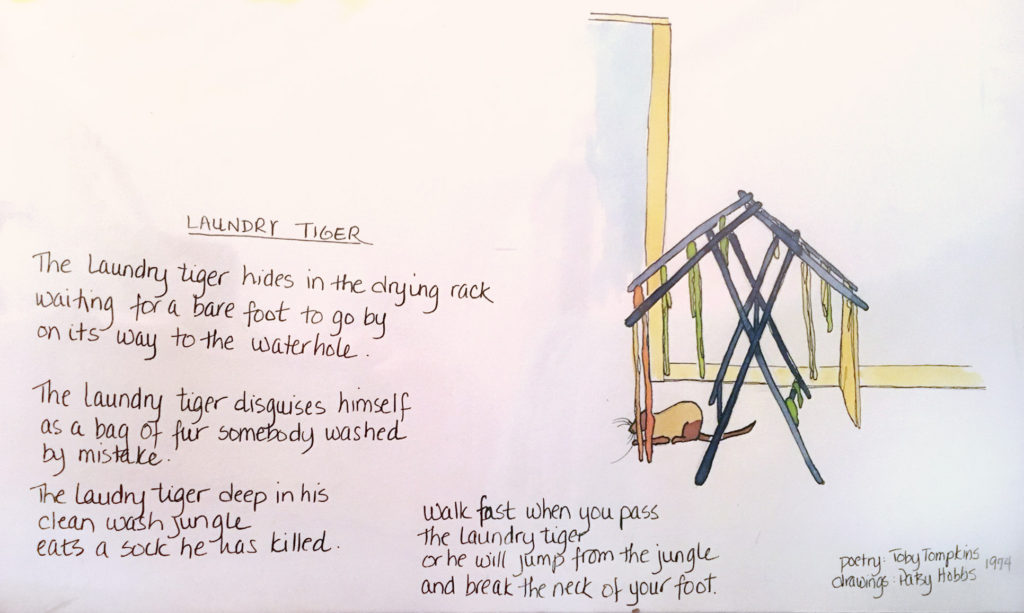

But cats always maintain hidden agendas, and although they enjoy the lives of ease their human companions provide, bland comfort isn’t enough for them. They’d rather be prowling around looking for new kinds of mayhem. They’re adventurers, bandits, desperadoes; in western movie terms, if dogs are the decent, honest white-hats, cats are the sneaky, devious black-hats. Years ago I wrote a poem about our first Siamese, Chispas, who used to lurk under the freshly-washed laundry as it dried on a rack in the hall of our apartment:

The laundry tiger hides in the drying rack

waiting for a bare foot to go by

on its way to the waterhole.

The laundry tiger disguises himself

As a bag of fur somebody washed

by mistake.

The laundry tiger, deep in his

clean wash jungle,

eats a sock he has killed.

Walk fast when you pass

the laundry tiger,

or he will jump from the jungle

and break the neck of your foot.